Steady Hands at the Helm: Ten Months In, Sir Jim Mackey Sets a Calmer Course to End Corridor Care

Practical leadership, hard metrics and zero tolerance for corridor care set a new standard for delivery

A quiet reset at NHS England where operational discipline, not grandstanding, is becoming the most powerful reform tool in the system

Ten months into the top job at NHS England, Sir Jim Mackey has not tried to dominate the headlines or launch a manifesto of sweeping restructures, and that absence of theatre may be the most consequential leadership decision he has made. Instead of slogans and summits, he has chosen something far less glamorous and far more difficult, which is to cool the temperature, tighten the focus and ask the service to get better at the basics that determine whether patients are treated safely or left waiting in places that were never meant for care. In a system long addicted to initiatives, that restraint feels quietly radical.

Spend time with chief executive officers and chief operating officers across the country and a consistent picture forms, not of a crusader or a technocrat but of someone disarmingly normal, someone grounded and practical who speaks in the language of wards, flow and staffing rather than frameworks and decks. One COO laughed when I asked what sets him apart and said he sounds like one of us, not like a consultant passing through with slides. Another described him as direct and down to earth, the sort of leader who tells you plainly what needs fixing and then expects you to get on with it. These are people responsible for the overwhelming majority of operational performance and the lion’s share of hospital spend, leaders who have lived through every wave of management fashion and who have developed a finely tuned radar for jargon. They tend to tune most of it out. Mackey is harder to ignore because he sounds like someone who has actually run a hospital on a winter Monday when every bed is full and the ambulances keep coming. Compared with previous eras often recalled with a weary shake of the head and the phrase a lot of hot air, what they recognise now is credibility, and in the NHS credibility travels faster than any mandate or memo.

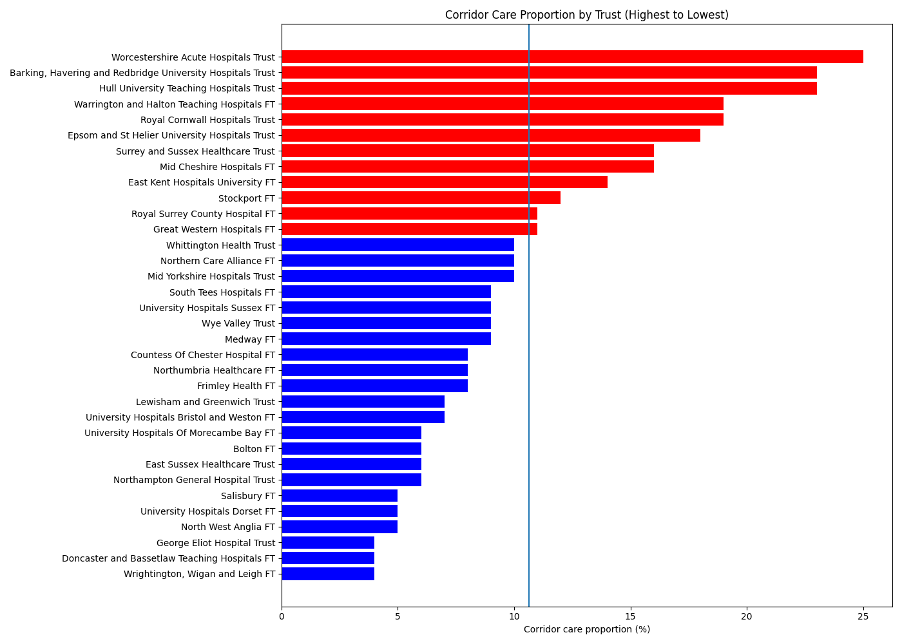

That credibility explains why his focus on corridor care has landed not as a crackdown but as common sense, because the scale of the issue is already impossible to ignore. Across England, hundreds of thousands of patients each year experience treatment in corridors, side rooms or other improvised spaces when emergency departments overflow, and more than half a million instances have been recorded by the acute trusts that disclose their data. In some hospitals as many as one in five patients spend part of their emergency journey in an environment that compromises privacy, dignity and sometimes safety. These are not abstract metrics on a dashboard. They are grandparents on trolleys under fluorescent lights, families trying to have difficult conversations within earshot of strangers, nurses improvising care in spaces designed for transit rather than treatment. No one who works in the system believes this is acceptable for a modern health service. Mackey’s framing is strikingly free of accusation. He is not asking who to blame. He is simply saying we can do better than this and we should, and that plainspoken standard is proving more persuasive than any directive could be.

For readers in the C suite, corridor care is not merely a reputational problem but the most visible symptom of deeper operational strain, a red warning light that tells you the entire machine is under stress. It signals that the front door is blocked because beds are full, that discharges are late because community capacity is thin, that social care is stretched, and that staff are working miracles just to keep the system upright. The corridor is where all those pressures collide and become visible. One emergency physician described it to me as the maths made visible, because if patients cannot move through the hospital then the backlog does not disappear, it simply spills out into hallways where everyone can see the consequences. When you frame it like that, corridor care stops being an unfortunate side effect and becomes a daily operational failure that demands attention with the same seriousness as infection control or mortality data.

In conversations with leaders last week, Mackey did not issue threats or set artificial deadlines. Those in the room say the tone was measured, almost reassuring, the kind of conversation that acknowledges reality rather than pretending it can be wished away. He recognised how brutal the past few years have been, from pandemic recovery to workforce gaps to relentless demand, and he spoke openly about the pressure of running hospitals with finite resources. Then he asked for focus. We cannot accept this as business as usual, one attendee recalls him saying, and another remembers the line that drew nods rather than groans, if we can count it we can fix it. There is something quietly powerful in that mindset because it assumes competence rather than failure. It says the problem is knowable and therefore solvable. No theatrics, no blame, just disciplined operations applied consistently.

Professional bodies have been equally clear. Royal College of Nursing has repeatedly warned about the impact on dignity and safety, while Royal College of Emergency Medicine has said corridor care puts lives at risk. Those statements are not campaigning rhetoric so much as clinical reality, and they reinforce the idea that this is a standards issue as much as a capacity one. Mackey’s approach aligns closely with that sentiment because he is not looking for clever rebranding or new terminology, he is looking for fewer patients in spaces that compromise care and more patients in beds where staff can do their jobs properly.

What is striking is how many local leaders describe feeling supported rather than pressured. Several used the word enabling. One chief executive told me she left her meeting feeling clearer, not heavier, while another said he makes you feel like you can fix it rather than like you are about to be blamed for it. That distinction matters enormously. Fear rarely improves operations because it drives problems underground. Clarity, by contrast, tends to surface them. By framing corridor care as a shared operational challenge instead of a failure to be punished, he has created space for honest conversations about flow, capacity and trade offs, the kind of conversations that actually change behaviour.

Those conversations inevitably return to fundamentals that would not look out of place in a hospital management handbook from twenty years ago. Discharge earlier in the day so beds free up when demand peaks. Know exactly where every patient is and what the plan is for each of them. Simplify pathways that have grown tangled over time. Work properly with community and social care rather than hoping someone else will pick up the slack. None of this is glamorous and none of it fits neatly into a press release, yet it is the quiet craft of management that determines whether patients are treated safely. One COO joked that the strategy sounds suspiciously old fashioned and then smiled and said it is basically just run the hospital well. Sometimes that is precisely what is needed.

There are early signs that the attention is paying off. Some trusts now review every corridor placement in real time, treating each one as a learning opportunity rather than something to hide. Others have created small command centres that track discharges hour by hour so decisions happen sooner. In several systems the simple act of measuring and discussing the issue daily has reduced reliance on corridors because teams intervene earlier and coordinate better. Capacity has not magically appeared, yet flow has improved because behaviour changed. Attention, it turns out, still works.

Politically the issue remains sensitive. Department of Health and Social Care has described care in corridors as unacceptable and undignified and is investing in urgent and same day services, but money alone does not create flow any more than a new dashboard guarantees performance. Leadership sets the tone and consistency sustains it. Mackey’s instinct seems to be that the tools already exist within the service and that the real task is to use them reliably, day after day, until good practice becomes routine rather than exceptional.

Perhaps that is why so many chief executives and chief operating officers speak about him with a kind of understated warmth. It is not hero worship so much as relief that the conversation feels grounded again, relief that someone at the centre understands that the NHS is run through thousands of small operational decisions rather than grand speeches, and relief that the ask is reasonable and human. Protect dignity. Keep patients out of corridors. Do the basics well. No fireworks required.

Ten months in, that may be his quiet achievement. He has made a very simple standard feel non negotiable without sounding heavy handed and has reminded the service what good looks like while trusting its leaders to deliver it. In a health system that has seen more turbulence than most, those steady hands on the wheel may prove more transformative than any dramatic reform. If fewer families find themselves waiting in corridors over the next year, it will not be because of a grand revolution but because someone calmly, persistently and credibly asked for better and the people who run the service decided he was worth following. Sometimes the most effective leadership barely raises its voice, and that might just be the point.

Chart source to reference in the article

Corridor care and emergency department overcrowding figures derived from NHS situation reports and urgent and emergency care performance data published by NHS England, supplemented by trust level disclosures collated by Royal College of Emergency Medicine.