Within the NHS, Palantir is no longer an abstract technology supplier but a familiar presence in national data infrastructure. Its platforms underpin parts of the federated data environment, support operational planning, and help link datasets across trusts, systems and national bodies. Against that backdrop, new reporting about historical financial links between Peter Thiel and Jeffrey Epstein has begun to circulate in policy and governance discussions, raising questions that are less about technology performance and more about trust, oversight and institutional risk.

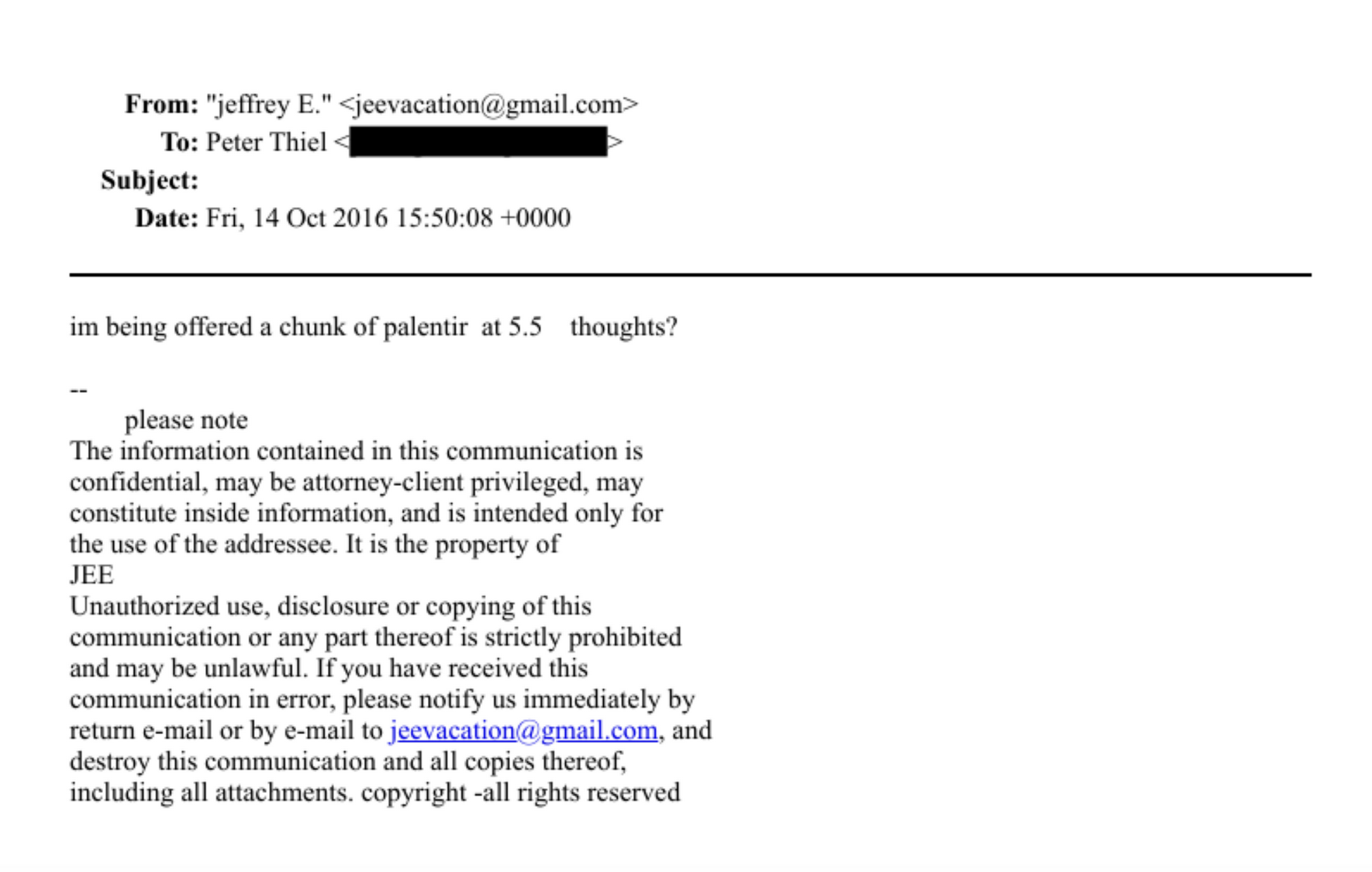

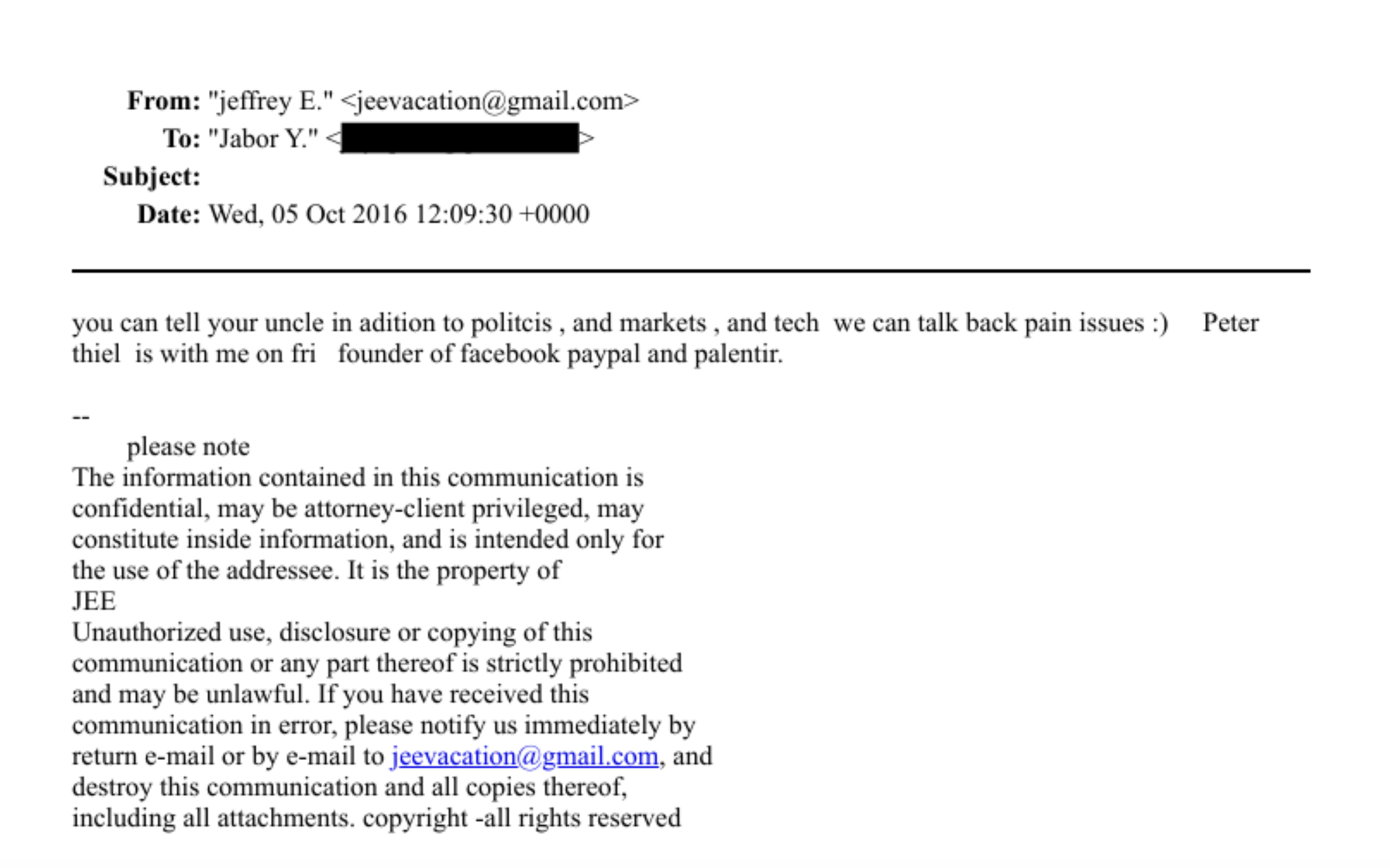

Documents released in the United States indicate that Epstein invested heavily in a venture fund run by Thiel’s firm, Valar Ventures, between 2014 and 2019. Representatives for Thiel state that Epstein was a limited partner rather than a co owner, but the association has drawn renewed attention because Palantir now sits within critical UK state infrastructure, including defence systems and NHS data architecture. The issue is not operational disruption but reputational and governance exposure.

For those working inside the NHS, the central concern is predictable. Public trust underpins everything from data sharing for direct care to participation in research and system planning. When the NHS asks patients to allow their data to flow across organisational boundaries, it depends on confidence that information is handled responsibly, securely and in the public interest. Controversy involving a major data partner, even if indirect, can complicate that trust landscape.

There is also the familiar question of control. NHS organisations understand the practical benefits of large scale data platforms, particularly for capacity management, elective recovery, urgent care flow and population health analytics. At the same time, long term reliance on a small number of external technology providers inevitably raises strategic questions about sovereignty, exit capability and the balance between public infrastructure and private vendors. These debates have existed since the earliest national digital programmes and are not new, but current developments may sharpen them.

Governance will likely be where most attention falls. The NHS has spent years strengthening information governance, procurement transparency and conflict of interest management, particularly where former officials move between public roles and private sector advisory work. Any renewed scrutiny of relationships surrounding major suppliers tends to trigger internal reflection across boards, regulators and arm’s length bodies. The system is used to this cycle, but it reinforces the need for visible safeguards and clear decision making.

From an operational perspective, nothing changes immediately. Palantir tools will continue to support planning, coordination and analytics across parts of the NHS. There is no indication of any compromise to patient data or service delivery. However, at national level, the discussion may influence future procurement posture, contractual transparency and the ongoing debate about who ultimately controls the infrastructure of NHS data.

For those inside the service, the underlying issue is familiar. Digital capability matters, but legitimacy matters just as much. The NHS can run on sophisticated data platforms, yet it ultimately runs on public confidence. Maintaining that balance between technological dependence and institutional trust remains one of the defining challenges of the modern NHS.